I have always been fascinated by the incredibly strange things that people have learned to eat through time in order to extract the maximum amount of nutrition from even the most desolate of environments.

And, it has been rewarding to repeatedly attempt to shed myself of my inherent cultural biases that defines “normalcy” in my diet and try to contextualize why people eat what they do. To step outside of our comfort zones to try to truly see other dietary practices from an emic, or insider perspective is difficult, considering our perception of food and the place it holds in our lives are so intricately intertwined with everything that we are and everything that we do. But, when we are able to do this successfully, so many aspects of other people’s dietary practices take on entirely new meanings!

The Search for the Ash Yogurt

Several months ago I met Dave and Sue Brown and Delia Stirling at David Ascher’s Traditional Cheese Making course in Iceland. After spending a week together and learning about all of the things we have in common – from our love of traditional raw milk cheese to foraging to ancient stone tool technology – they invited me and my family to visit them in Kenya where they operate Brown’s Cheese and spend time working with traditional groups to learn about their contemporary foodways still based on ancestral practices. After I returned home and mentioned this to my family we jumped at the opportunity – and, I am so incredibly glad we did!

Preparation for our visit required months and Delia took on the majority of the planning herself. It was during this time that I kept stressing to her my desire to learn about mursik, a traditional yogurt made with ash in the West Pokot County of Kenya and, if at all possible I also wanted to experience the blood-letting practice of the pastoralists such as the Samburu. After much work, Delia devised an itinerary that would accomplish all that I wanted and also included the added bonuses of camping in the bush and multiple safaris at Lewa House! We were all in, and the next few months seemed to drag on forever as we anxiously anticipated our adventure to begin.

We started our journey to Kenya after a short visit to Johannesburg where I was presenting at the 2018 ACE, the first Experimental Archaeology Conference held in Africa. Despite the multiple flights, layover in Ethiopia, and hour-long drive to Brown’s Cheese from the Nairobi airport, our expedition to find people producing mursik was just beginning. After one day’s rest we woke up early and drove an hour in the dark through pouring rain to Wilson Airport where we boarded a small, propeller plane and flew to the more remote area of Kitale. There we were greeted by our driver, Samuel who would unexpectedly would also later turn out be be our guide.

As we sat around Cranes Haven Lodge that evening discussing the research plan for the next day that Delia had arranged with Slow Food Kenya, Samuel overheard us and suggested we travel to the lowlands, further and deeper into the West Pokot area to find people less influenced by modern western diets. There, he told us, we would find what we were searching for – people still actively engaged in production and consumption of mursik because they still relied upon it as an important component of their daily diets. And, he assured us that we could also learn how to make traditional honey wine and how the people of West Pokot slaughter and butcher goats and eat their small intestines raw. This sounded great! However, it was already 10:00 pm and didn’t know how we would make it all work on such short notice. With cell phone in hand, Samuel calmly replied that he knew people and could make it happen. He just needed our go-ahead to “activate his network” to make it happen. “Activating his network” cost us a little more than we anticipated (and included the purchase of two goats!), but it was worth it because thanks to Samuel and his network, the next day was better than we ever could have ever imagined.

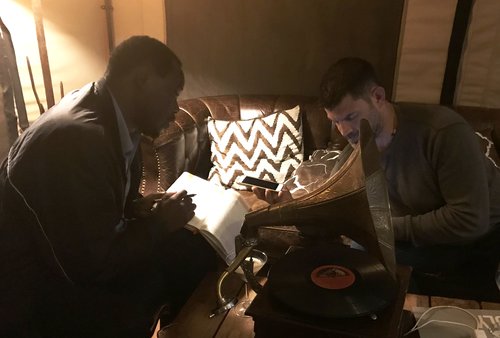

Bill and Samuel working on “activating his network” at Cranes Haven Lodge The wonderful Cranes Haven Crew!

Setting off to Find Mursik

The day started as planned and, after driving a couple of hours we met with the Kenya Slow Food International representative, Sampson, at the Horizon Hotel who took us to the Tarsoi Village for our first mursik experience of the day. Sampson explained to us that the Tarsoi Village is actually made up of two separate village, the Tartar and Soibei whose names combine to make Tarsoi (sort of like Benifer – Ben Affleck and Jennifer Garner – but longer lasting…). The drive from the hotel to the village was much shorter than I expected. However, since the paved road quickly changed to dirt and the rectangular concrete block buildings became round wattle and daub thatched structures the scene quickly met our expectations. We parked the cars and waiting for someone to come greet us my sight focused on the fence like metal contraption whose purpose it was to funnel cows into a narrow concrete shallow pool filled with some sort of disinfecting liquid meant to sterilize their legs, bellies and udders. I thought it out of place for a village that we spent so much time and effort getting to in order to learn more about traditional diets.

We heard them from a distance before we saw them… the sound of the singing and the bells and then the bright colored clothing and the dancing.

It looked as though the entire village was coming to greet us. Over the next 20 minutes, through the magic of music and dance, we were transformed from spectators into participants.

We were then escorted to an open grassy area where the villagers had brought a couch from one of their homes for us to sit. As they gathered around one of them led us in an obligatory prayer. Then, through the help of an interpreter, the chairman told us the story of the Tarsoi, welcomed us, and thanked god for the kromwo tree, the tree that they burn to obtain the ash to make the mursik, for the medicinal value it brings to them. Afterward he also thanked the milk for the medicinal value it brings them. Then he thanked Slow Food because of them, he said, they have been to Italy to show people in other parts of the world how to make the mursik. Finally, he asked us to go around and introduce ourselves and for each of us to let everyone know why we were there. Only after we had become a part of the process through the ritual of music, dance and prayer and introduction were they ready to share with us their traditional food, mursik.

The Traditional Process Revealed

We were brought into a small, round, wattle and daub kitchen with a compact dirt floor. There, three women were huddled around a small fire burning in the hearth. One held the end of a stick in the fire until the tip was glowing red. She then stuck the charred end into the gourd all the way to the base and scraped it up along the inside to the top with more pressure than I would have expected.

This resulted in leaving a black streak of ash behind in its path. This scraping motion was repeated once or twice and then the stick was returned to the fire until it once again glowed red. The stick was then placed inside the gourd and the scraping motion resumed for a stroke or two. The repeated scraping inside the gourd and burning in the fire continued until the entire inside of the gourd was coated with black ash. Excess ashes were shaken out and then the gourd was filled with cows milk. Immediately, the ash coating inside the gourd changed the bluish/white color of the milk to a speckled grey. A lid made from the cut-off end of the gourd that utilized a coiled natural cordage twined base that fit snugly over the base was placed on top, and the gourd was set aside to ferment. As soon as the gourd was set down, indicating the end of the process, I began to bombard them with questions…thankfully they were so incredibly generous and patient with their answers.

This is what I learned:

- The ash is essential to the process because a) it imparts a flavor and the mursik simply does not taste right without it, b) it changes the color and look and the mursik does not look right without it, and c) it provides a medicinal value since it is basic versus the acidity of the fermented milk.

- The stick they burned and used to scrape the inside of the gourd they called “kromwo” its genus and species is Ozoroa insignis. They insisted that the mursik can only be make from a stick from this tree, however, they could not tell me why other than it, “has different properties” and the fact that it forms theproper coal. In the few instances they can recall not being able to obtain a stick from the kromwo tree they substituted with wood from a native olive tree. I assume this is the tamiyai or, Olea africana.

- Once the gourd is filled they set it aside to ferment for anywhere from 3 days to 3 months depending on several factors including how much surplus milk they have. Typically, once the gourd is filled and the milk has fermented for at least three days it is ready to drink. Before it is consumed the gourd is shaken. After consumption, the gourd is refilled with new milk and, because the residue from the previous mursik is still alive and active with strong bacterias that were built up during the fermentation process the fermentation of the new milk will only take a day or two!

- The milk they used was pasteurized. Wait, what? As soon as I heard this Delia and I immediately shot a look at one another. We are both cheesemakers who deal with raw milk and utilize traditional methods and understand what this means and how dangerous it is. Raw milk is naturally full of the active bacteria that produces the fermentation. When the fermentation begins through this process the pH drops and kills off harmful pathogens in the process. However, the pasteurization process does not discriminate between good and bad bacteria and kills it all leaving behind a blank slate. There is nothing there to initiate the fermentation nor any good bacteria left to fight harmful pathogens. That is why modern cheesemakers using pasteurized cheese MUST add a culture of bacteria to the milk to begin the fermentation. Blank slates such as these are easily colonized by harmful bacteria that have nothing stopping them from taking over and creating a very dangerous situation.

INTO THE LOWLANDS

Other than a nagging, uneasy feeling over their use of pasteurized milk, I felt I accomplished what I set out to do – see mursik production, taste/experience mursik, and observe how mursik production and consumption is influenced by and is an important part of their culture. Nevertheless, Samuel was urging us to say goodbye and load up in the vehicles quickly to provide us enough time to drive all the way to the lowlands. His promise of an even more traditional mursik experience was romantic and we followed his advice, thanked everyone for sharing such an important part of their lives with us and left.

The drive was rough…in fact, it was the hottest, bumpiest, scariest drive I have ever experienced anywhere in the world! Recent intense and persistent rains had washed out the sandy dirt roads and our descent down the side of the mountain was risky. There was no guard rail and not much left of the road. I was seated right next to the window on the side of the vehicle closest to the edge and, with a clear few of the shear several thousand foot drop and there more than a few times I thought we were going off the road – and there was no chance whatsoever of surviving. I wondered if this was the right choice and what kind of father I was to put my family in this sort of danger. For what? We had already experienced the mursik. Was it worth it to go this far to witness something a little more traditional? I seriously wondered if my family was going to survive this experience but it was too late to turn back. Stopping and attempting to turn around would have been more dangerous than just continuing down the mountain. We were committed.

Eventually, after almost three hours of descending down the mountain we reached the lowlands and the roads flattened out. The dirt roads were not in any better shape, but at least we no longer faced the danger of falling down the escarpment. A while later we turned off the road and drove into the bush eventually stopping at the entrance to a village.

And again, we heard it before we saw it – the villagers came out to greet us with song and dance!

The songs were different, but the enthusiasm the same.

We were all quickly surrounded and, through hand and eye gestures invited to participate. Once we did we worked our way as a group through the gate. The singing and dancing lasted for about 20 minutes and seemed like every person in the surrounding area participated. It wasn’t until the music stopped that I realized I was mistaken.

Our driver-turned-guide, Samuel, approached me and pointed out the man in the distance – the single person not participating. He was laying on a rawhide mat in the shade of a tree with his head resting on a carved wooden headrest. There was a look on his face of complete indifference and he refused to make eye contact with any of us. I thought it strange that with all of the festivities – singing and dancing and laughing – that he was positioned where he was in an almost angry state. Samuel informed me that this is Kadel, the head man and that it is my responsibility to go to him and introduce myself before he would acknowledge any of us. As Samuel, Jason and I walked over Kadel remained steadfast with his eyes seemingly focused on something in the distance. Whatever he was looking at was not us. I spoke first and, and through Samuel, thanked him for allowing us to visit him and his people. A moment passed and then he spoke as Samuel translated. Kadel asked me to introduce myself and to tell him why we had come – which I did. As Samuel tried to keep up with my enthusiastic response I told Kadel what I did and all about the Food Evolutions Project and the Eastern Shore Food Lab at Washington College that I was building and how excited I was to learn more about the mursik at a level that would allow me to inform others of this important food that is so integral to the health and well-being of his people in West Pokot. I wished to develop strategies where I could adapt the approach to make something similar with the resources local to the Eastern Shore of Maryland while meeting the requirements of the local food health and safety standards – an almost insurmountable task unless the process is fully understood.

When I finished, he stood up and approached me. My eyes caught the ring knife he wore on the ring finger of his left hand. I had never seen anything like it before and the intense sun reflected off of the polished metal surface making it look even more ominous. I didn’t know what to expect, but as he approached me he generously reached out his right hand to greet me and we shook. At that moment everything changed – a smile came across his face and his eyes brightened. We began to joke and laugh and I brought him over to introduce him to my family and the rest of the group.

Our 1st Taste . . . Honey Wine

The rest of the visit was incredible. We started by drinking honey wine made with the sausage tree fruit to celebrate our visit and, of course there was ritual associated with this practice as well. One man was in control of the gourd that contained the honey wine and how the wine was distributed. After removing the plug of branches and leaves that kept the flies out of the wine he spread them out on the ground. He filled a long, thin bottle gourd with wine and, then, before drinking any wine whatsoever, he ceremoniously sprinkled drops on the ground as an offering to the ancestors. Then, he began to pass the gourd around to drink. The first recipient, my 10-year old daughter, Alyssa who was taken aback both by the opportunity to drink alcohol and the bits of dead bees and bee parts, wax, and sticks floating on the surface. After a few awkward glances she took an obligatory sip and passed the gourd along. Contrary to her experience we all enjoyed the honey wine, some perhaps too much! And, with the added benefit of the social lubrication offered by the honey wine we proceeded to learn how they make their traditional mursik.

They prepared the gourd in a very similar fashion at the Tarsoi, except, that it is first rinsed with cow urine and then scraped with a burning end of a stick also from the Kromwo tree. However, the biggest difference is that they fill the gourd with raw milk and set it aside to ferment.

Typically, it is consumed around the 3-7 day mark, however, when there is a surplus it is set aside to ferment for much longer period, sometimes for over 6 months and is known as cheposoyo. It loses quite a bit of moisture over this period and becomes more like cheese than yogurt. During times of huger a spoonful of the concentrated cheposoyo is mixed with water and drank. Two servings of this is sometimes the only food consumed each day!

Then they offered us several month old mursik made from raw goat’s milk – it was amazing! The flavors and textures were complex but welcome. There was absolutely no off or strong taste and even the kids went back for seconds! It is hard to believe that the only ingredients were ash and raw milk fermented in a gourd cleaned with cow urine!

So…after my short but intense experiences with Mursik this is my take:

- The ash in “ash yogurt” isn’t ash after all, but rather charcoal

- They are not making yogurt, but instead clabber

- After watching the process of coating the inside of the gourd with ash/charcoal I think there is a possibility that the practice of using the burned stick to add ash/charcoal to the fermenting milk was not initially for dietary or medicinal purposes.

Certainly, the presence of the ash/charcoal impacted the flavor, texture, and presentation (look) of the mursik, introduces important minerals to their diet and, it provides medicinal value, but I think something the practice provides which is more basic that has nothing to do with the ash/charcoal is why they first started to do it and continue to this day – the heat of the burning coal cleans the gourd and gets rid of unwanted pathogens. And, this is why – after watching the process several times, I was struck as how often the stick is returned to the fire until the end is glowing red. Then, the stick is used to scrape the inside of the gourd only a couple times before it is returned to the fire to burn some more. This repeated returning to the fire only to scrape a couple times is more than necessary to produce enough ash/charcoal to sufficiently coat the inside of the gourd. Every time they stuck the stick in the gourd smoke escaped out the opening revealing just how hot the stick actually is! Also, the inside of the gourds are somewhat rough and porous and I believe a combination of the heat and the pressure they use when they scrape helps the “fibers” of the inside of the gourd compress resulting in a smoother surface and, perhaps the ash/charcoal fill some of the pores.

If this is correct, then over time the flavor, texture, and look of the mursik would become the standard and requirements for “proper” mursik. It simply would taste right, or look right, or have the right mouth feel without it. However, if the addition of the ahs/charcoal was only for dietary or medicinal purposes why not just directly add the ash/charcoal into the milk?

Of course something has to happen on a plane ride . . .

The next day as we boarded the tiny plane in Kitale to return to Nairobi I proudly clutched the gourd that had held the 3-month old goat milk mursik beautifully decorated with cowry shells I received from Kadel the day before. And, it was that gourd that the four impeccably dressed men who boarded the plane with us noticed and prompted them to ask us who we were and what we were doing. Taken aback, I explained all about the Food Evolutions project and the Eastern Shore Food Lab to, who is turns out, were the West Pokot Governor, Chief of Staff and two other government officials travelling to Nairobi on government business. They were excited about what we were doing, why we were doing it and so thrilled to share their traditional food practices with the outside world! When we landed in Nairobi we exchanged contact information and they invited us back and hoped I would bring Washington College students next time!

WAIT TILL YOU SEE OUR NEXT STOP IN KENYA!

– Here’s a hint to see what we drank with the Somburu!!

Making the Most of your Animal: What Nose to Tail Can Really Be

Making the Most of your Animal: What Nose to Tail Can Really Be

Well placed and am glad to be of help in the research thank you to Dr. Bill the family and his friends. True the organization was limited.