Recently there is more polarizing dialogue over human diet and health than ever before, and as a result, navigating the modern human dietary landscape has never been more confusing. On one side of the argument a vegan diet is advocating an animal-free, wholly plant-based for health of the planet and our species. On the other, a meat-based, carnivore diet is purported to be the answer and some supporters of this approach go so far as to suggest that there are entire groups of plants that we should not be consuming because they contain toxins. All of this is absurdity, and any diet that is so orthorexic and exclusive is not in line with the dietary approaches that built us as humans both biologically and culturally. One of the biggest issues with the justification of such dietary practices is that the story is often incomplete. When a larger picture is revealed the context shifts the entire game changes.

The study of our dietary past reveals a story that is exactly the opposite from any of the aforementioned approaches that blatantly exclude large categories of food – through time our ancestors have developed ways of INCLUDING an increasingly rich diversity of foods from their environment into their diets and, most importantly, developed technologies to make them safe, nutrient dense, and bioavailable for the human body!

Thankfully, there are still some pockets of people around the world still processing food in similar ways to their ancestors and I am committed to learning as much as possible directly from them before their technologies disappear and are lost forever.

A day at my type of “office”

I just returned from conducting research in Bolivia and Peru living with and learning from two incredible indigenous families (one Aymara and the other Quechua) that still rely upon traditional approaches to detoxify potatoes and other staple plants in their diet. In addition to making food safe, nutrient dense and bioavailable these processes also transform the flavor, texture, odor, and character in ways that make these foods culturally significant!

P’ASA – ONE OF THE THINGS MISSING FROM OUR MODERN HUMAN DIET, IS….DIRT!

Many animals consume earth …and our ancestors were no different. Animals (and people) consume earth/clay for its nutritional and medicinal value as well as its ability to detoxify food! In fact, many animals that eat plants also eat earth as a way to render the toxins in the plants safe.

Wild potatoes and many ancient heirloom varieties have high levels of toxins including glycoalkaloids. Low doses of glycoalkaloids will result in abdominal pain, diarrhea and bloating. High doses can result in paralysis and death! The Aymara, indigenous to the Altiplano region of the Bolivian and Peruvian Andes, are one of the few remaining groups still practicing geophagy. They dip potatoes in clay as they eat them during a practice known as P’asa because the clay binds with the toxins in the potatoes allowing them to safely pass through our digestive tract while they simultaneously reaping the nutritional and medicinal benefits.

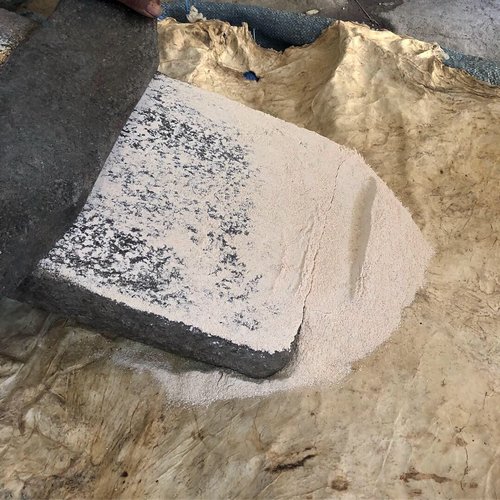

The process begins with building an earthen hornito or oven, fueling it with cow patties (there are almost no trees in the area) and cooking the potatoes. Then, the potatoes are dipped in a mixture of water, salt and clay and are eaten directly. The process and result are so enculturated into their lives that they now use it for numerous varieties of potatoes – not just the toxic ones.

An array of native potatoes ready to be roasted Enjoying my 1st potato dipped in clay!

CHUÑO BLANCO

A very interesting time and labor-intensive process, perfectly suited for the climate of the Altiplano region of Bolivia and Peru simultaneously detoxifies potatoes and transforms them into a unique food known as chuño blanco. To make chuño blanco, potatoes are loaded into net or mesh bags and submerged in a river for 30-60 days. During the time they spend in the river they are detoxified and transformed through both fermenting and leaching. The length of time they spend in the water is determined by a number of factors including the variety of potato and the desired result. Potatoes are ready for the next step based upon their odor.

When they come out of the river they are incredibly soft and mushy and need to be handled carefully. They are spread out on the ground in a single layer not touching one another to freeze overnight so that they become firm enough to remove their skins without compromising their integrity. The next morning, while still frozen, they are placed into a large container with a little bit of water and stomped, almost like grapes but with an added “twist” of the feet. Instead of crushing, the motion of the stomping work to essentially “peel” the potatoes and, since the potatoes are still frozen, they remain whole. They are then placed in a net or mesh bag, rinsed several times to separate the skins, then the potatoes are laid out once again on the ground to dry for several days.

Once dried they will store for years and are reconstituted by steaming or boiling, or ground into a “flour” and used as the basis for a number of delicious and nutritious traditional dishes.

TOCOSH

At lower altitudes in the Peruvian Andes freeze-drying is not an option. Instead potatoes are fermented for a long period of time to create tocosh. In addition to detoxifying, the extended fermentation process completely transforms the potatoes into nutrient dense and bioavailable morsels that convey strong and very interesting flavor, odor, and textural properties. It is also claimed to convey a host of medicinal benefits. And, as you can imagine there is an abundance of lore supporting these claims. These qualities are highly desired by people that enjoy tocosh and, as a result, a whole variety of potatoes – containing all levels of toxicity are used.

To create tocosh first a 5-meter-deep pit is dug in the ground. It is lined with straw and then filled to the top with 600 kilograms of potatoes. Another layer of straw is then laid down to cover the potatoes, followed by cloth or empty sacks. Finally, large rocks are place on top of the bags and the pit is filled with water to cover the potatoes. The pit is checked daily to ensure the water never drops below the level of the potatoes. This creates an anaerobic environment for the fermentation. The minimum amount of time needed to complete the process is 6 months, but the tocosh I sampled was fermented for 2 years! After it is pulled from the pit it is left to dry for a day and then peeled by hand. It can be eaten as it, roasted, or, most commonly boiled into a very interesting and incredibly nutritious porridge to which sugar, squash or quinoa is often added.

QUINOA

Even the “superfood”, quinoa contains toxins including saponins, phytic acid and tannins. Saponins are remarkably stable and are not removed through cooking. However, that does not mean we should not eat this food. Instead, it can be detoxified by scrubbing and rinsing in multiple changes of water. The saponins that are released through this process are so strong, in fact, that after finished rinsing the quinoa the rinse water is used to wash clothes here in the Altiplano region of the Andes!

Some of the quinoa you purchase in the US has been detoxified already for you – however, the industrial processes used to make the quinoa safe are too harsh and result in also removing some the most nutritious parts! It is best to purchase unwashed quinoa and do the washing at home yourself.

Grinding Quinoa on stone Finished Quinoa flour

THE BEST APPROACH

It is true that plants contain toxins such as lectins and phytic acid, but that does NOT mean we should exclude them from our diet! These plants’ chemical defenses are no different than their physical defenses. Should we not eat nuts because they have a hard shell that our hands and teeth are not adapted to breaking through? No! Instead of excluding nuts from our diets our ancestors overcame their own physical limitations that prevented them from accessing the nutrient rich nut meats on the inside by developing technologies that allowed them to crack hard shells (smashing the nut between two rocks!). Until recently, we as a species have always done the same with plants’ chemical defenses (toxins). To overcome various plants chemical defense mechanisms, our ancestors developed technologies such as fermentation, geophagy (intentional consumption of earth), drying, leaching, and cooking to overcome the physical limitations of our human digestive tract, in this case the inability to safely consume certain plants and instead detoxify otherwise poisonous plants and allow us to safely derive nutrition, medicine and pleasure from consuming them. We need to relearn and reconnect with the food processing technologies from our deep dietary past and rich dietary present still extant in traditional societies around the world and rekindle our approach to food. It’s not just about what you eat, but also HOW you eat it!

Dr. Bill with Aymara family in Bolivia (2019) Dr. Bill with Quechua Family in Peru (2019)

Fermentation Nation Camp

Fermentation Nation Camp

[…] how one can nixtamalize corn with an alkaline answer to make masa dough in Oaxaca, researched potato detoxification with Indigenous Bolivians, and drank uncooked milk and blood with pastoralists in […]