Cheese has always fascinated me.

Ever since I was a young child I have loved everything about the experience of eating cheese. I loved the way it looked, the way it tasted, the way it smelled (well, most of it), and I even loved the texture. My parents also love cheese – and growing up we always had some version of it at home. Thankfully, they never fell into the trap of eating highly processed cheese. No. In our family Velveeta wasn’t considered food, at least for humans. Instead, we used it as bait when we went trout fishing (it makes an amazing trout bait!). American cheese? Well, that wasn’t fit for anyone’s consumption! The cheeses with which my mother kept the fridge stocked were mostly comprised of mild flavored cheeses including Cheddar, Monterrey Jack and Colby. That said, my father could never resist his provolone – a trait that he has passed down to me. I can still remember vividly looking forward to attending functions as a child on my Italian side of the family since they always had a cheese platter containing large cubes of provolone! Without fail my father would always proclaim his catch phrase, “Provolone, sleep alone!” as he and I both downed cube after cube. My sister and I still repeat it (albeit sometimes in our head depending on the company we are in) every time we eat provolone cheese.

Cheese was a major component of practically any foray into the kitchen as a child.

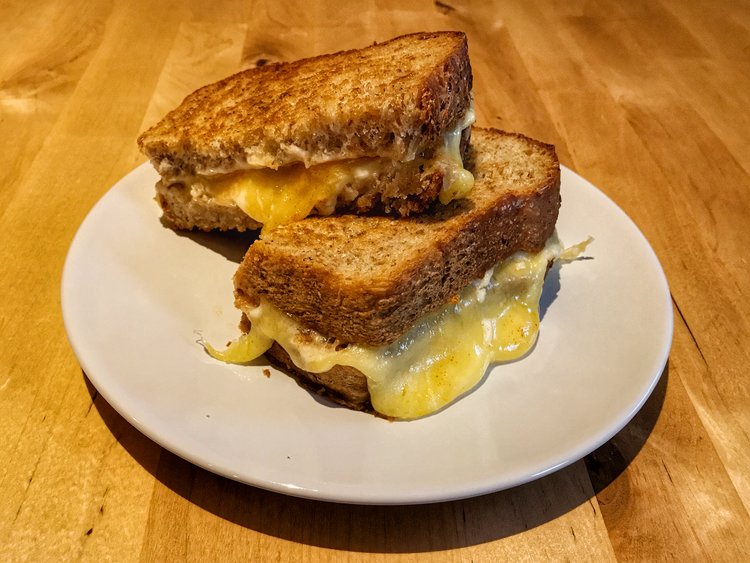

One of my fondest childhood cooking memories was preparing eggplant parmesan with my Italian Grandmother, Teresa, which, of course, would not be eggplant parmesan if there wasn’t cheese! I loved how cheese always “made” any sandwich complete and can still taste the gorgeous grilled cheese sandwiches my Granny would make us as kids to accompany tomato soup – she would take the darkest, healthiest looking sandwich bread she could find, lather the inside with mayonnaise sprinkled with curry powder, add thick slices of aged cheddar cheese and sometimes a slice of tomato or ham, cover with another piece of bread then smother the outside with butter and brown each side in a hot pan. You couldn’t beat the aroma of the curry as you bit into the thick sandwich just to feel the “bite” of the not-completely-melted cheese on the inside. It was nothing like the grilled cheese sandwiches my friends had at home made of Wonder bread, covered in margarine, with completely melted American cheese on the inside.

My Granny’s sandwich had character, it had body. There was something there when you bit into it.

I didn’t realize it then, but this was a completely different food than what my friends were eating that impacted everything about the eating experience from the flavor, texture and presentation to the nutritional quality of the food.

On the occasion that we had blue cheese in house, I even loved that! The flavor, smell and texture intrigued and scared the hell out of me at the same time. What was so strange to me is that even with this, perhaps the strongest smelling and tasting foods we had in our house that owed everything about what it was to the presence of mold, we not only put it in our mouths, but savored it! We didn’t know anything about how it was made and, for some reason felt we didn’t need to. We were willing to give up the control of our food to an “expert” we didn’t know but assumed understood how to safely handle milk, mold, and the entire cheese production process. We trusted that these people we never met were making a safe food, that they knew how to package and label the cheese, and they knew how to get it to grocery stores. There was always a mystic surrounding cheese – perhaps because there were so many unanswered questions… How did the holes get into Swiss cheese? How did the “blue” get into blue cheese? Why did some reddish/orange rinded cheeses smell really bad, like feet, and why was it okay to eat it? Why did some cheeses melt and some did not?

Cheese also held great culinary promise because it was so versatile!

Cheese was equally at home on a plate for breakfast, lunch, dinner, a snack or even dessert? It can be paired with wine and even beer! It can immediately transform a bland food into something savory and render something seemingly inedible to a toddler into something to relish. All of this said, I would guess that of all major real food categories go cheese may be the one we know the least about (yet still love the most!).

When the traditional loses to convenience . . .

These multitude of questions surrounding cheese has both elevated cheese to a special place in the world of food and also allowed it to be taken over by a set of “specialists” that have essentially bastardized cheese to the point that it has become a completely different food than it used to be. This is what happens when traditional foods get taken from the home and become a product of commercial and industrial kitchens. Slowly, traditional knowledge is lost, power and control is handed over to “specialists” and eventually we are duped into believing this is “progress” and the “burden” of producing our own food has been replaced by the seemingly welcomed convenience of someone else taking on the responsibility. Unfortunately, the real results of this is a complete disconnection from our food and, because of this separation food production happens in a space to which no longer have access. In that space very, very scary things can happen. The result? What we are experiencing right now – food that is both unhealthy and a system that is not sustainable. We need to regain that control and home cheese making is a fantastic model for how to do this with a food that most of us know absolutely nothing about – but should.

My personal quest begins . . . Oh my poor wife!

Almost 20 years ago I began a personal quest to learn as much as humanly possible about fermentation and dove head-first into the subject. Within a few weeks, much to my wife’s dismay, I had jars and crocks and bowls filled with vegetables, grains, dairy, and even alcohol bubbling all over the house. I was strongly influenced by early on by Sandor Katz, the author of, “Wild Fermentation: The Flavor, Nutrition, and Craft of Live-Cultured Food” and began to make all of my ferments wild – they were to be cultured by wild yeasts and bacterias. My sauerkraut and kimchis were fermented using wild bacteria. My sourdough bread was made from a wild culture. Even many of my alcohol ferments – mead (honey), cider (apples), wine (grapes) and beer (barley) were fermented with wild yeasts. The one area in which I was not fermenting with wild cultures was with dairy. Why?

I knew there had to be a way to ferment dairy using wild cultures, but I just could not find any information about it. I scoured the internet, YouTube, and the book stores. Every time a new book about cheese making was published I immediately ordered a copy – but was soon disappointed when it arrived because it was just repeating the information found in the other books I already had on my bookshelves. The recipes required me to purchase freeze dried cultures and pre-made rennet available only from a handful of cheese making equipment suppliers. The freeze-dried culture world was a very confusing one – there were cultures specific to cheeses made at room temperature (mesophilic) or high temperature (thermophilic). There were cultures specific to different types of cheeses such as chevré or feta. Some of the cultures could be directly added to milk and others needed to be cultured first. There were also other powdered things I was told I need add to cheese for different effects such as lipase powder or citric acid.

My cheese making interest quickly became expensive and my freezer filled with silver foil packets full of cultures that I desperately tried to keep dry (an almost impossible task given when taking something from a freezer to room temperature and back again – condensation quickly builds up). Any moisture whatsoever will ruin the culture. Since there were so many cultures specific to different cheeses I never finished any of them before they reached their expiration date requiring me to go back and purchase more. Despite this seemingly endless variety of freeze dried cultures there are primarily only two manufacturers worldwide. And, most of the cheesemakers around the world use cultures from these two companies. Something was wrong. Why did I feel so “un-empowered” to make cheese? Why did I need to rely on “professionals” to supply me with what I needed and to tell me what to do? Why did it seem like suddenly all the varieties of cheese specific to individual regions around the world were different from one another more because of the freeze dried culture the cheesemakers bought as opposed to something different about the region such as their terroir or their history? Where was the magic in cheese that I had felt since a child?

EVERYTHING SEEMED SO STERILE, SO SCIENTIFIC. EVERYTHING SEEMED: JUST. NOT. RIGHT.

So, where did cheesemakers in the past, without access to freeze dried commercially available cultures, obtain the bacteria from which to make their cheese? No matter how hard I looked I could not find answers to this question. I wondered why this was so difficult to answer and, more importantly, what else would the answer to this question bring with it concerning history, tradition, health, empowerment, and terroir???

The same holds true for rennet – there are only a few producers of animal rennet around the world. Rennet is a very natural product made from the enzyme chymosin which is derived from the stomachs of unweaned mammals. It is essential to almost all cheese making because it separates milk into curds and whey. It is difficult for young mammals to completely digest liquid milk in order to extract the maximum amount of nutrition. Instead, chymosim curdles the milk in the stomach and transforms the liquid into a semi-solid state which slows down the flow of the milk through the developing digestive tract allowing it to be more fully digested using the body’s physical and chemical processes. And yes, off course, this even happens in human babies! If you have ever had a baby spit up on you and wondered why what came out of their mouth looks like cottage cheese, now you know!

Successfully running a dairy requires impregnating animals to initiate milk production and, once they are born and the mother’s milk comes in some of the young animals, especially males, are slaughtered for their meat to ensure there is enough milk to operate the dairy. Since most cheese making requires rennet to separate the curds and the whey, and the calves provide a consistent supply of chymosin (rennet) in their stomachs, the system seems to make sense. Sadly, no. That is not the case. The reality is that it is almost impossible to get the stomach back from the abattoir or butcher – even when it is your own animals that you brought to them for processing! Since these stomachs are discarded the only option for cheese makers using natural rennet is to purchase it. Most rennet available is made from veal calves that are slaughtered in New Zealand and their stomachs shipped to Austria for processing then sold around the world in powder, liquid and paste forms.

Something just seemed wrong . . .

Why did I need to rely on multi-national corporations to supply me with the ingredients to make traditional cheeses? How can all of my other ferments bubbling away on my counter tops rely solely on wild bacteria and/or yeasts and require nothing beyond the most basic of raw ingredients, some salt, and a vessel in which to ferment. I searched for answers in my books, but all of my cheese making books contained lengthy discussions about sterilization, precise measurements of specific cultures which they suggested were necessary to make each different type of cheese, the need for expensive thermometers and ph meters, and advocated the use of only stainless steel or plastic. They put the fear of god in me with their warnings about raw milk and made me question, time and time again, the fact that I only fed my family raw milk. In fact, I go to great lengths to drive hours each way to Pennsylvania, where it is legal to purchase raw milk, with which to make the dairy products I was feeding my family. Something just was not right – there had to be a safe way to transform raw milk, using equipment found in the home, into these dairy products. After all, the archaeological record suggests that people have been transforming milk, a perishable food, into a storable, nutrient dense, more bioavailable product that had very pleasing yet diverse tastes, smells and textures for at least 7,500 years. These butters, cheeses, kefirs, and yogurts became very important food resources for people around the world both nutritionally and culturally. BUT, they did not have to rely on special freeze-dried cultures and rennet only available from specialty mail order shops. They did not have to sterilize their equipment with dangerous chemicals. They did not have ph meters. Where was the wild fermentation for dairy???

The first major advancement in my own cheese making occurred last year.

I had the opportunity to attend an intensive week-long cheese-making class at the Italian Culinary Institute (ICI) in Calabria with Chef John Nocita. Chef John is an amazing chef and a talented and passionate teacher. Through this course I was immersed in Italian cheese making history, tradition and technique. And, throughout the course of the week we made approximately 20 different traditional Italian cheeses! I left that week bursting full of so much knowledge that I immediately had to share it with as many people as possible.

Cheese Takeover at Home

After I returned home, I immediately got to work and finished building the cheese cave in my basement. It is a temperature and humidity-controlled 6×6 foot room where I can experiment and make all types of cheeses regardless of the climate in Maryland. Some people might call it a large closet, but the insullated walls, humidifiers and temperature control system make it the perfect environment for aging cheese.

I also got to work right away and began teaching my students at Washington College everything I had learned at the ICI and worked with them to produce a variety of cheeses to highlight the Eastern Shore Food Lab as a part of the Washington College capital campaign!

Learn More About the Campaign Dinner

Making my Italian Grandmother Proud!

Perhaps most importantly, I was able to share the Italian Cheeses I had made after returning from the Italian Culinary Institute including Mozzarella (well, really, Fior di Latte since it was made from cow’s milk and not buffallo), Caciocavallo, Ciocotta, Grana Padano, and Tomini with my 92-year-old Italian grandmother! This was a special moment and, unfortunately, she recently passed making that the last opportunity to share something that I had created her.

Thank you, Chef John, for empowering me to share such a meaningful gift with her.

Still on a quest for raw milk cheese

Italy has an incredibly rich cheese tradition – they have over 350 different types of cheeses subdivided into about 1,000 varieties. However, just like the rest of the world, today many of them are now produced using pasteurized milk requiring the addition of a commercial culture. This is beginning the change. In addition to the home cheese makers that have carried on raw cheese making traditions there are some incredible modern cheese artisans bringing back raw cheese to Italy. In fact, Italy recently hosted the Bra Raw Milk Cheese Festival attracting raw cheese makers and enthusiasts from around the world. Learning to work with raw milk was still very important to me and I have been on the quest to learn even more.

Then I got an alert from Amazon that notified me of a new cheese making book available titled, “The Art of Natural Cheesemaking: Using Traditional, Non-Industrial Methods and Raw Ingredients to Make the World’s Best Cheeses.” Could this be what I was looking for? Would this answer my questions and empower me to free myself from having to rely upon huge corporations to supply me with what I needed to make my cheese?

A few days later when the package from Amazon finally arrived I enthusiastically ripped it open and sat down to read it cover-to-cover, excited but prepared to be disappointed like I had so many times in the past with the other cheese making books that promised to empower me to make “real, artisan cheese” at home. Hours later when I finished I set the book down and realized that he had done it. The author, David Asher, had answered my questions and empowered me to make cheese the way I had been dreaming of doing. And, of course, when he explained the real, traditional processes of cheese making it was all much easier than I thought…

Over the next several months I worked my way through the book making most of the cheeses he described and rereading sections over and over again. I learned more from this one book than all of the other books combined. But, I still had questions. There was still so much to learn. David did an excellent job of describing each process, but there is no substitute for watching an artisan’s hands as they work. Or smelling and tasting milk through the different stages of the cheese making process. I wished I was able to learn directly from him.

Learning as much as possible about traditional cheese making is a priority for me this year for two very significant reasons.

- My sabbatical research and professional development is focused on preparing to launch the Eastern Shore Food Lab at Washington College. Traditional cheese making will comprise a major component of the food lab as this ancestral technology is in line with our mission and will be used as a basis for the development of new local traditions that celebrate terroir and local resources of the Eastern Shore food shed.

- As a part of the Food Evolutions project, obtaining a better understanding traditional cheese making is necessary to better understanding the ancestral foodways of Ireland. Ireland has one of the oldest traditions of cheese and butter making in the world. However, over time, the tradition of making cheese has been lost and has only recently been reintroduced.

I am convinced that a thorough comprehension of traditional cheese and butter making technologies is necessary in order to make the fullest use of the archaeological record to accurately interpret ancient foodways in Ireland.

This year my wish came true!

I took full advantage of the opportunity to take a 5-day intensive cheese making course with David Asher in Iceland. This course was organized by Erna Skúladóttir and took place in her coffee shop/pottery studio “Bragginn” located in Flúõir, about 2 ½ hour drive from Reykjavík. Our work area for the course was the enormous potato storage room adjacent to the coffee shop that was dug into the hill behind it. The course drew participants from all over the world including the United States, Canada, Iceland, Ireland, and Kenya!

It quickly became apparent that this course was exactly what I was hoping it would be. We learned all about the properties of raw milk and how to safely work with it. David showed us how to control the cheese making process to harness the naturally occurring microflora in the milk, just like cheese makers have been doing for thousands of years, so that we did not need any of the freeze-dried starter cultures. In fact, he showed us why it made much better cheese to do so!

Over the course of the week we used his methods to produce dozens of different cheeses from all over the world!

Perhaps the most profound message that David conveyed to the class was when he asked us to consider the cheese making vessel, literally the pot of milk, to be symbolic of the stomach of an unweaned animal. Almost everything that we do in cheese making is actually meant to mimic the environment that is created in that stomach. After all, the stomach of an unweaned mammal essentially makes cheese out of milk in order to ensure that the baby animal is getting the most amount of nutrition it can from the milk. This was a true lightbulb moment for me and allowed me to conceptualize cheese making in an entirely comprehensible way.

I don’t know whether it was that statement or the fact that I always try to create soul-authored teaching and learning experiences whenever possible, but one day after class I pulled David aside and asked him if we could go through the process of making our own rennet. A little startled he turned to me and asked if I realized that it would mean killing and butchering a young veal calf? I told him of course I did and that I just did not feel like I was making traditional cheese unless I started at the very beginning and participated in the entire process. He informed me that he had never done in any of his classes before, but since he realized the importance of the experience for the class he thought it was a fantastic idea. However, he had two very important concerns that needed to be addressed before he agreed. The first was that there was someone skilled enough to ensure that the animal died quickly and humanely and that it would be butchered in such a way to preserve the stomach so it could be made into rennet and all of the animal would be used for food. I said that I had a lot of experience hunting and butchering and would be willing to do it. In fact, I actually needed to do it because it would finally close the loop I had been waiting to close for so long.

The second concern was that he needed to make sure the entire class was on board. And, he was right. Killing and butchering an animal is very emotional and, while experiencing this visceral act in the proper way is one of the most responsible things that we as omnivorous human can do, it needs to be contextualized and approached properly for it to be a worthwhile experience instead of a nightmare. He suggested that were not yet at the place in the class to be able to bring this up to the group and that he would wait a few days. David has been teaching traditional cheese making for a long time and he has learned how to organize his courses so that themes build on one another in a way that allows him, over the course of a week, transform the way people look at both cheese and the modern food industry. I witnessed this unfold over the course of the week. Conversations on the first day were comprised of the typical, food-related topics that were important, but really only scratched the surface. Over the next few days we all became better informed and began to speak what I can only describe as a more common language and the conversations took on an entirely new meaning. It was then, once the group more fully understood the reality of what it takes to successfully run a dairy and to make real cheese, that he could offer the opportunity to obtain our own rennet. As you can imagine, the entire group was ready and willing.

We purchased a two-week old veal calf from the neighboring dairy that was already scheduled to be slaughtered. After quickly dispatching and bleeding the animal we hung the calf and began to skin it. I was working with two other participants in the class – David and Sue – fantastic cheesemakers from Kenya, who have experience slaughtering and butchering their own animals. Once the animal was skinned the three of us removed the organs and spread them out on the table. We were after the fourth stomach chamber – the abomasum – because this is where the milk gets curdled and from where we can obtain the chymosin. The other stomach chambers are still developing in a mammal of this age and when a young calf feeds the act of stretching its neck positions its digestive tract in such a way that the milk flow directly to this fourth stomach bypassing the others. When the milk reaches the fourth stomach it comes in contact with the chymosin (rennet) and curdles.

The fourth stomach chamber can be located because it is the last organ before the small intestines. Once we removed the abomasum we realized that it was full and most of the contents were semi-solid – cheese!!!! After straining the contents we washed out the stomach and put it on salt to begin the curing process. What remained in the strainer was the cheese the calf’s stomach had produced – naturally. There was a special connection with the past that very moment. It is easy to see how someone in the past had put two-and-two together when they witnessed this phenomenon for themselves after butchering a young animal and seeing the contents of its stomach. They would have realized that there was something special about that stomach and perhaps all they needed to do was take a piece of the stomach and place it in fresh milk and they could control the process themselves. It wouldn’t have taken them long to realize that they could actually make cheese outside of the animal’s body and control the process to produce different results. Since they were using raw milk they could ferment the cheese using the natural microorganisms found in the milk, separate the curds and whey using the rennet from the animal’s stomach, and control for nuances such as time, temperature, humidity, curd size, and pressure to produce different results. The specifics ways in which various cultures over time accomplished this produced in the large variety of cheeses around the world. All they had to do was to consider the cheese making vessel to be symbolic of the stomach of an unweaned animal.

As we stared at the strainer we realized there was one thing left to do…sample the cheese. After all, this was truly a naturally made cheese. In fact, it is the original cheese. Certainly, all of the participants in the class had digested cheese that our own stomachs produced when we were infants in order to digest our mother’s milk properly. However, none of us have had the opportunity to actually taste it since it was produced in our stomachs after we ingested the milk. I broke off a small piece and put it in my mouth. The texture was pleasant, sort of like a strained ricotta. And the flavor? Well, it was reminiscent of a super strong provolone, a trait most likely due to the presence of the lipase enzyme that helps break down fats that also provides provolone with its strong flavor. This gave an entirely new meaning to my father’s phrase, “Provolone, sleep alone!” The taste stayed with me for several hours and, even though strong, it was a constant reminder of this opportunity that connected me with the first cheesemakers thousands of years ago.

Gallery of Pictures from David Asher’s Cheese Making Course

Want to learn more?

CONTINUE EXPLORING AT:

Fermented Shark: Bucket List Item Checked Off!

Fermented Shark: Bucket List Item Checked Off!

Leave a Reply